Note: while I personally disagree with this article, as the purpose of this amendment was, in-fact, to pull together 3 enacted laws to grant citizenship & protect the previously known slaves. The heart of this (section 1) argument is is a fallacy, misinterpretation & misapplication of the fourteenth amendment. The heart of the Constitution grants an ordinal class of citizenship to its people. (Ref to: Citizenship)

August 26, 2015

Michael C. Dorf

ImmigrationLast week, Donald Trump released a white paper on immigration reform. It proposes, among other things, to “end birthright citizenship.” Trump himself should not be taken seriously as a presidential candidate, and it should be noted that his draconian views on immigration are controversial even within the Republican primary field.

For example, in response to Trump, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush characterized birthright citizenship as “part of our noble heritage.”

Still, Trump’s tough-on-immigration position appeals to many Republican primary voters. Moreover, as his white paper trumpets, even Democratic Senate minority leader Harry Reid once supported ending birthright citizenship. Accordingly, those of us who think that children born in the United States to undocumented immigrants are properly deemed citizens cannot simply ignore Trump’s proposal as attention-grabbing buffoonery.

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment

In the U.S. context, the term “birthright citizenship” refers to the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which begins: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.” That language was added to the Constitution following the Civil War in order to overrule the infamous Dred Scott decision, which declared that African Americans could not be citizens. However, like other provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment, the language of the Citizenship Clause is general: by its terms, it does not apply merely to former slaves and their descendants but to “all persons born” here.

The Trump white paper does not say how Trump intends to end birthright citizenship. Some people who oppose birthright citizenship call for a constitutional amendment, but other reformers suggest that no amendment is needed. The Citizenship Clause, they note, is limited to those persons “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States and they argue that children of undocumented immigrants do not satisfy this criterion.

As a textual matter, that claim is odd. As Professor (and Verdict columnist) Ronald Rotunda noted in a 2010 Chicago Tribune op-ed, undocumented immigrants are indeed subject to the jurisdiction of local, state, and federal government—as are their children. If they break the law, they can be prosecuted just like anybody else.

What does the Fourteenth Amendment mean when it refers to people who are born here but not subject to U.S. jurisdiction? The Supreme Court answered that question in the 1898 case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark. Riding a wave of nativist racism against East Asians that bears an uncomfortable resemblance to the anti-Latino sentiments that contemporary immigration hawks sometimes express, Congress enacted and then re-enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, which placed severe restrictions on the entry into the United States of Chinese persons—including, in the view of the government official who sought to exclude Wong Kim Ark, ethnic Chinese who had been born in the United States.

The Court rejected the government’s attempt to apply the Chinese Exclusion Act on the ground that Wong Kim Ark was a U.S. citizen, even though his parents remained subjects of the Emperor of China. Justice Gray’s majority opinion relied mostly on the common law and practice that formed the backdrop for the Fourteenth Amendment. That backdrop also informed the Court’s understanding of the Amendment’s express qualification: Children born in the U.S. to foreign ambassadors and consuls, or to soldiers or others accompanying invading armies had, by tradition, not been regarded as citizens, as they were not “subject to” our law. But otherwise, people present in the U.S. are subject to U.S. laws and, for that reason, most people born in the U.S. are U.S. citizens.

Yet Wong Kim Ark’s parents were in the U.S. legally when he was born. No Supreme Court case affirming the broad scope of birthright citizenship speaks to the precise question of the citizenship of children born to undocumented immigrants. And in their 1985 book Citizenship Without Consent: Illegal Aliens in the American Polity, Peter Schuck and Rogers Smith relied on an 1884 Supreme Court case holding that Native Americans are not entitled to birthright citizenship to question the broad language of Wong Kim Ark as applied to children of undocumented immigrants.

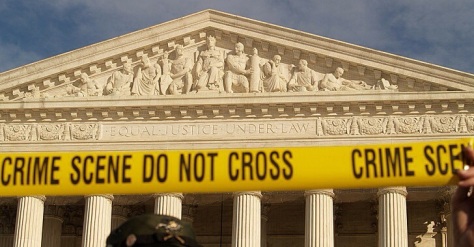

Thus, if immigration liberals are comforted by the apparently clear implications of the language of Wong Kim Ark, we should remember that before the Supreme Court dignified the claim that Congress lacks the power to require people to purchase health insurance, that claim too was widely dismissed as essentially foreclosed by prior precedent. We should not underestimate the ability of clever lawyers to make off-the-wall arguments sound reasonable—especially if they end up arguing before a Supreme Court that includes new Justices appointed by a future get-tough-on-immigration president.

The Virtues of Birthright Citizenship

Should the opponents of birthright citizenship fail to get what they want by persuading or packing the Supreme Court, they would need to amend the Constitution. What can we say to persuade Americans that such an amendment would be a bad idea?

The best defense of birthright citizenship echoes the position espoused by the Supreme Court in the 1982 case of Plyler v. Doe. Texas tried to deny a free public education to the undocumented immigrant children living in that state. In holding that the state thereby violated the Constitution, the Court noted that the state’s approach was illogical. As Justice Powell explained in a concurrence, no one “benefits from the creation within our borders of a subclass of illiterate persons, many of whom will remain in the State.”

So too with citizenship itself. If we are not going to deport the millions of people born here to undocumented immigrants—and we are not—then there is little reason to withhold the sense of belonging and the concomitant sense of duty that go with citizenship.

Many countries, including countries generally regarded as democracies, reject birthright citizenship, treating parentage as the chief means of acquiring citizenship. As Professor Rotunda noted in his Op-Ed and as Professor Neil Buchanan discussed in his recent column on the Dominican Republic’s treatment of its ethnic Haitian minority, this approach can be ugly. Generation after generation of people who have known no other home are treated as not even second-class citizens.

By contrast, birthright citizenship implements widely shared and characteristically American values. Through the Titles of Nobility Clauses of Article I, Sections 9 and 10, the Constitution abjures eighteenth-century European notions of privilege obtained by birth. Meanwhile, Article III, Section 3 forbids the “Corruption of Blood”—the old practice of disinheriting the heirs of persons convicted of treason or other serious crimes. Together, these provisions reject the proposition that in America the sins of the fathers (or mothers) can be visited on the sons (or daughters).

That notion also informed the Supreme Court’s decision in Plyler. “Even if the State found it expedient to control the conduct of adults by acting against their children,” Justice Brennan wrote for the majority, “legislation directing the onus of a parent’s misconduct against his children does not comport with fundamental conceptions of justice.”

No doubt the American commitment to disregarding accidents of birth has always been under-inclusive, originally grossly so. After all, the original Constitution co-existed with race-based chattel slavery, and we still face the consequences of our collective failure to fully remedy that historic wrong.

But the Fourteenth Amendment—including its Citizenship Clause—was a huge step in the right direction. Curtailing its promise of birthright citizenship would thus be a huge step backward.